By Ron Thiessen, Executive Director, CPAWS Manitoba

A profound love of nature and of his Dene people drove Ernie Bussidor to protect the Seal River Watershed. His charisma and his passion helped transform a vision into reality.

Manitoba lost a champion of nature when Ernie died in his sleep on January 27, 2024 at the age of 67. And I lost a friend.

I first met Ernie when he flew to Winnipeg in early 2016 to raise the alarm about the volume of caribou being harvested near Tadoule Lake.

Harvesters from far away drove up the winter road in huge trucks that they filled with thousands of caribou.

They did not respect traditional hunting practices, Ernie told a meeting of the Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak. Cows were killed, their fetuses dumped like garbage in the snow.

Rounds and rounds of gunfire cast a pall over a community meeting about a settlement with Canadian government for the relocation of Sayisi Dene First Nation in the 1950s and 1960s.

Listening to Ernie speak, it was obvious why he was serving his community as chief for the third time.

Ernie was a born leader and storyteller. When he spoke, people didn’t just listen. They were moved to take action.

I had been looking for an opportunity to meet with Sayisi Dene First Nation for a couple of years. Their traditional territory is one of the last great wild spaces on the planet.

The Seal River Watershed is a pristine expanse of tundra, wetlands and forests as vast as Denmark. There are no permanent roads. No dams. No mines. No industrial development of any kind. Caribou and polar bears roam beneath massive flocks of birds near a powerful river teeming with beluga whales, seals and fish.

So I introduced myself to Ernie at the Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak (MKO) meeting and asked if he would be interested in protecting the lands and waters in Sayisi Dene’s traditional territory. Was he ever!

A Friendship Based on Laughter and a Shared Passion for Nature

We became fast friends over dinner at the Best Western Hotel. We shared a passion for nature – and a similar sense of humour. He was kind, he was generous and he was a lot of fun to hang out with.

Ernie invited me up to Tadoule Lake to talk about what a protected area could mean for the Sayisi Dene. We received overwhelming support from council and then received an enthusiastic response at a band meeting in May 2016.

Ernie made sure I understood what we were working to protect: he showed me the beauty of the landscape and introduced me to the people who called it home.

A lifelong adventurist, Ernie knew these lands and waters well. He was among the first Sayisi Dene people to return to their homelands after decades of despair in Churchill following a forced relocation.

Ernie moved to Tadoule Lake in 1974 and set off on his first major canoe trip two years later, paddling from Lac Brochet to Tadoule. He cut a winter snowmobile trail from Tadoule Lake to South Indian Lake in 1978. He witnessed the destruction caused by hydrological developments on a 1986 canoe trip from South Indian Lake to Tadoule Lake. He spent long, dark days building winter roads from Lynn Lake to Tadoule from 1996-2000.

Ernie paddled the third and final branch of the Seal River in June 2017, on an epic canoe trip from Tadoule Lake to Churchill that helped connect the community’s youth to the land and waters as they navigated white water rapids and polar bears.

“I am fully amazed and still in awe of the beauty, ruggedness, and pristineness of this territory, Ernie wrote in an introduction to a 2022 report on the Ecological Goods and Services of the watershed. “An abundance of wildlife that uses this amazing river as its home can best be witnessed in the summer evenings when travelling by canoe.”

Ernie was also a deeply spiritual man, who spoke lovingly of the wisdom shared by his maternal grandparents – Dene elders Peter and Mary Bussidor – who taught him about his culture, his people’s history and how to hunt, fish and sustain himself on the land.

An Alliance of Dene and Cree Peoples From Four First Nations

We had spent much of 2016 and 2017 exploring the possibility of establishing a national park.

Two huge developments shifted our focus in March 2018: the federal government announced it would invest $1.3 billion in conservation initiatives and the Indigenous Circle of Experts published a report about Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCA) that transformed how conservation is pursued in Canada.

Sayisi Dene First Nation would no longer be asking the provincial and federal governments to protect their traditional territories. They could take the lead role in stewarding the watershed.

Before Ernie took things any further, he wanted to make sure that he had the full support of Sayisi Dene First Nation. That one band meeting in 2016 wasn’t enough.

Ernie went from house to house in Tadoule Lake. He spoke with band members about how an IPCA could transform their community. How it could help get youth out on the land and connect them with their culture. How it could help them recover from the intergenerational trauma of the relocation.

“I told the people that I want to protect our territory according to our rules and our customs, to create a protected area to keep hydro out, and to keep industry out,” Ernie recalled in a documentary released after his untimely death.

“So we took it from the grassroots up, and that’s where it stayed.”

More than 80% of Sayisi Dene First Nation’s on-reserve members signed a petition to “preserve the watershed from industrial development and to keep it in its pristine state for future generations to enjoy by creating an Indigenous Protected Area or Tribal Park to be managed by Indigenous leadership.”

But Ernie didn’t want Sayisi Dene First Nation to go it alone. He thought a protected area would be an opportunity to strengthen ties with neighbouring communities who also had ancestral ties to the watershed.

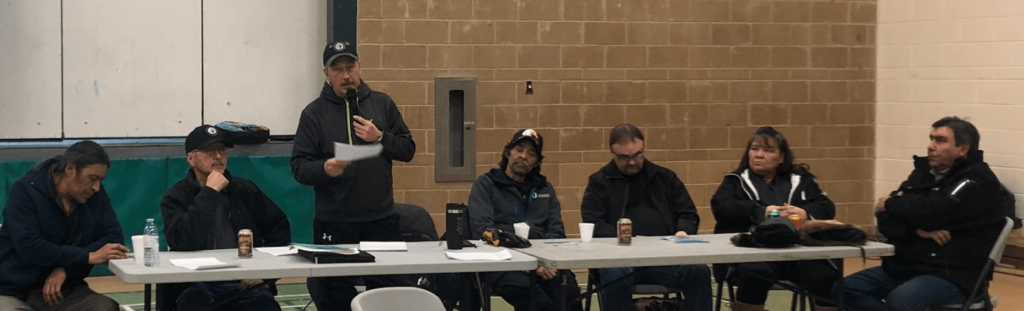

So we raised some funds and invited the chiefs of O-Pipon-Na-Piwin First Nation, Northlands Denesuline First Nation and Barren Lands First Nation to a meeting in Thompson in June 2018.

I’ve been working in conservation for more than 30 years. I have never seen such firm agreement happen so quickly on a matter of such great significance.

In just three days, the chiefs did more than just agree to the idea of a protected area: they drafted an agreement in principle that remains the foundation of the Seal River Watershed Alliance to this day.

Ernie invited me back to Tadoule Lake after the meeting in Thompson. We spoke to community members about the initiative. And Ernie showed me more of what we were working to protect. He steered me across the lake to a cabin he’d built by hand as a retreat for elders and he laid nets so I could taste the lake’s bounty.

Secure in the support of his community and of neighbouring First Nations, Ernie and I got to work on applying for the funding and political support needed to turn this vision into a reality.

A moment I will never forget the sound of Ernie drumming and praying in Dene on Parliament Hill in October 2018. We were in Ottawa for a caribou conference and used our time there to urge the federal government to invest in the Seal River Watershed Indigenous Protected Area Initiative.

Canada Invests $3.2 Million to Conserve the Watershed as an Indigenous Protected Area

The good news was announced in August 2019: $3.2 million in funding over four years to support the quest to preserve the entire watershed as an Indigenous Protected Area.

We were able to celebrate in Tadoule Lake a few weeks later at a stewardship summit of Dene, Cree and Inuit youth thanks to a separate grant secured by CPAWS.

We got to work on the initiative right away, not waiting for the contract to be signed or the first check to arrive. There was so much to do, and Ernie’s passion was contagious.

We hired a project manager and started meeting regularly with the Indigenous Leadership Initiative, who had been involved since 2018 and provided incredible levels of support for the initiative.

We reached out to chiefs and councils to identify community liaisons and lay the groundwork for the first leadership gathering.

We hired documentary filmmaker Al Code – whose children are members of Sayisi Dene First Nation and who spent 30 years living in Tadolue Lake – to produce a short video about the initiative using his archival footage. Then we kicked off the public campaign in November 2019 by inviting Al to screen the video at the CPAWS Manitoba annual general meeting.

An important step was establishing a working relationship with the Innuit of the Kivalliq Region who also have ancestral ties to the watershed, which extends into Nunuvut at its northernmost point. Ernie and I flew up to Arviat in November 2019 and were able to secure a letter of support from the Arviat Hunters and Trappers Organization.

We gained another key endorsement in Arviat: the Beverly and Qamanirjuaq Caribou Management Board unanimously passed a motion to support the establishment of Indigenous Protected Areas in general and the Seal River Watershed initiative in particular.

Ernie was grateful for the endorsement, but he was eager to visit neighbouring communities to meet with community leaders and to engage members in the initiative.

He met with off-reserve community members in Churchill in January 2020 while we were in town for a Parks Canada caribou conference, which also gave us a chance to connect with the Manitoba Métis Federation.

Our next stop was Northlands Denesuline First Nation, where more than 60 band members signed a referendum supporting the initiative at a community engagement meeting on February 4, 2020.

“Each of us – Dene, Cree and Inuit – all have stories of similar original and all have a richness of language and culture and history,” Ernie told the crowd gathered at Petit Casimir Memorial School in Lac Brochet.

“We should all learn from it, and show the world our resilience, and our fierce desire to keep our lands and waters intact and unspoiled,” Ernie said. “There is only so much wilderness left in the world, and this rare opportunity is being presented to us.”

Pandemic Impacts the Initiative

A few weeks before the pandemic turned the world upside down, we gathered again in Winnipeg for a remarkable meeting at the end of February 2020.

Leaders from five communities with ties to the watershed shared their Dene, Cree and Inuit cultures and languages. They spoke of their relationships to the lands and waters. And in just three days, they developed a vision statement and agreed to form the Seal River Watershed Alliance.

Advancing the initiative during the pandemic was exhausting. Ernie turned to radio bingos instead of band meetings to keep community members informed. We used Facebook contests to encourage members to share their views. We kept things moving by commissioning a public opinion poll, a carbon analysis, a bird report and an ecological goods and services report. A brief lull in the pandemic allowed us to host a leadership meeting in August 2021. But we all got worn down by zoom meeting after zoom meeting.

Ernie Passes Leadership to the Next Generation

I deeply admire Ernie’s willingness to step back from his role as Executive Director of the Alliance and make space for the brilliant Stephanie Thorassie to lead the initiative in September 2021.

“I’m at an age now where I can’t take on the workload or the stress of travelling and constant meetings,” Ernie said in the documentary We Are Made From The Land: Protecting the Seal River Watershed.

“And so we hired a young lady by the name of Stephanie Thorassie as an assistant one summer, and she was so efficient and so amazing, and she just kind of just walked into the perfect timing. And I convinced her to just take this project, take the young people, and do it as a younger generation project.”

Stephanie has the passion, presence and charisma to inspire everyone from community members to delegates at UN conferences. She has the patience to navigate complex negotiations with crown governments and the diplomacy and tact needed to take direction from the leaderships of four First Nations. She has the focus and the attention-to-detail needed to manage a non-profit organization.

Ernie continued to contribute in many ways, sharing his wisdom in his role as Senior Advisor and engaging youth and community members in harvesting and hand games.

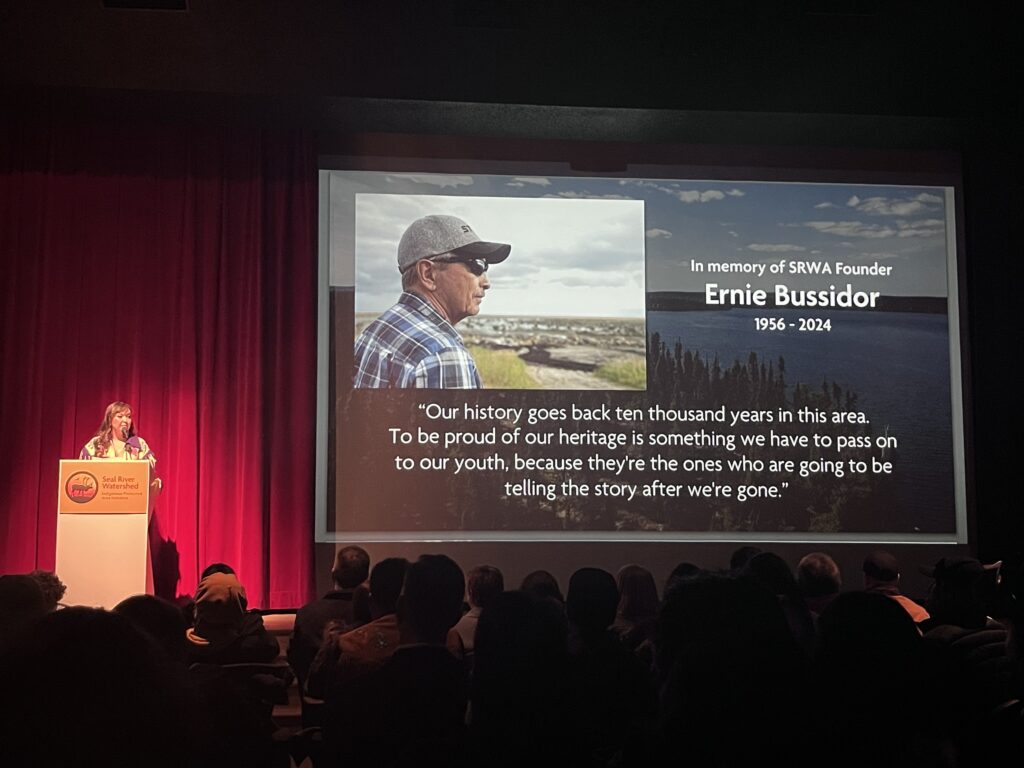

“The past and the future, these are two forces that inspired a man that I am humbled to honour tonight,” Stephanie said at the March 2024 premiere of We Are Made From The Land: Protecting the Seal River Watershed.

“Ernie was a dreamer who could inspire people around a shared vision,” Stephanie told the crowd gathered at the Winnipeg Art Gallery.

“May Ernie’s passion for self-determination, united voices and the love of family and the caribou continue to fuel this work and push and propel us forward.”

I wish Ernie had been able to join us in Winnipeg in January 2024 for the announcement that the entire watershed was granted interim protection while the governments of the Alliance Nations, Manitoba and Canada study the feasibility of establishing an Indigenous Protected Area.

We could never have gotten there without him.

I am so grateful, however, that Ernie was able to watch it happen from his home in Tadoule Lake. That he died with the knowledge that his vision will soon become a reality.

Ernie’s family was generous enough to share his response to a friend who congratulated him for the interim protection announcement.

“Aw, thanks, buddy. That’s uplifting. I can now continue on my spirit journey knowing my children and their children will have a safe and secure future.”