Connecting for Conservation Speaker Series Part 2: Paddling Past Polar Bears

By Kaitlin Vitt, Digital Marketing and Outreach Coordinator

Growing up in the remote northern community of Tadoule Lake, Stephanie Thorassie would join her dad in collecting wood to heat their home. In the winter, they’d head out on a snowmobile — their only mode of transportation across the frozen landscape besides a dog team — and as her dad would cut down trees to bring back home, she’d play in nature.

One time, she didn’t wear her mukluks, opting for other boots instead, and her feet felt frozen. So on their ride back home, her dad sat her down in front him on the snowmobile, turned her so her legs were facing him and lifted up his jacket so she could put her feet on his stomach to warm up.

“This was a part of normal life — being smart about how to live on the land, even as a young person,” said Thorassie, a member of Sayisi Dene First Nation.

Accessible only by airplane or winter roads, Tadoule Lake is the only community located in the 50,000 square kilometre Seal River Watershed. There are no permanent roads. No mines. No logging. The pristine watershed is full of life, including at least 23 known species at risk, such as polar bears, beluga whales and wolverines.

Stephanie Thorassie prepares a moose hide for tanning. Photo courtesy of Stephanie Thorassie.

Sayisi Dene First Nation is leading an initiative to protect the entirety of the Seal River Watershed from industrial development as an Indigenous Protected Area in partnership with its Cree, Dene and Inuit neighbours. Partnership and support for the project is also provided by CPAWS Manitoba and the Indigenous Leadership Initiative.

“We have a strong sense of responsibility and passion toward needing to protect the area so that it can be used for generations to come,” Thorassie said in a webinar hosted by the Seal River Watershed Alliance and CPAWS Manitoba.

“We want to keep it pristine, and we want to share it with others in a way that’s healthy and positive for everybody without creating too much dependency on the land.”

Accounting for eight per cent of Manitoba and 0.5 per cent of Canada’s land mass, protecting the Seal River Watershed would help Canada to meet its commitment of protecting 30 per cent of the country’s lands and waters by 2030.

The Relocation of Sayisi Dene First Nation

In 1956, the Canadian government forced the Sayisi Dene to leave their traditional territory at Little Duck Lake in the Seal River Watershed after wrongfully accusing them of overhunting caribou.

There was a river near where they lived that was also a caribou crossing, Thorassie explained. In fall, the Sayisi Dene would hunt there and leave the caribou on the shores. When winter came, it created a sort of natural freezer, and families were able to feed themselves even after all the caribou left the area, since they had this store of food.

“Since time immemorial, the Dene people have been doing this,” Thorassie said. “We’ve been providing and living off the land harmoniously.”

But someone came and took a photo of the caribou carcasses, and rumours started to spread about caribou being overhunted.

The government blamed the Sayisi Dene for the allegedly declining caribou population and forced them to relocate to Churchill, which is where Thorassie’s parents were born. It was later determined that the reported decline in caribou was simply part of a normal population cycle, Thorassie said.

The Canadian government formally apologized in 2016 for the forced relocation of the Sayisi Dene. About one-third of the relocated Dene died “as a result of poverty, racism and violence,” the Manitoba government said in a 2010 apology for its role.

“The Sayisi Dene were forced to live in this new boomtown where life wasn’t like what they knew, wasn’t like the nomadic lifestyle that they lived before,” Thorassie said. “People couldn’t survive. They couldn’t feed themselves. They couldn’t live off the land; therefore, their spirit was missing.”

Eventually, the Sayisi Dene decided to move back to the area they lived before — the Seal River Watershed. And by 1973, they relocated to Tadoule Lake.

When Thorassie’s father Roger arrived in Tadoule Lake from residential school, he thought he had died and gone to heaven. He didn’t know such a beautiful place existed.

You could hunt and fish to feed your family, find wood to make fires and drink water straight from the lake. This was a stark contrast to her father’s experience growing up in Churchill, where he had to find food at the dump to survive.

The Seal River Watershed Alliance

Ernie Bussidor, who was chief at the time, was inspired to conserve the watershed after meeting CPAWS Manitoba Executive Director Ron Thiessen in 2016. Shortly after, Sayisi Dene First Nation and CPAWS formed a partnership and launched an Indigenous-led initiative to protect the watershed from industrial developments.

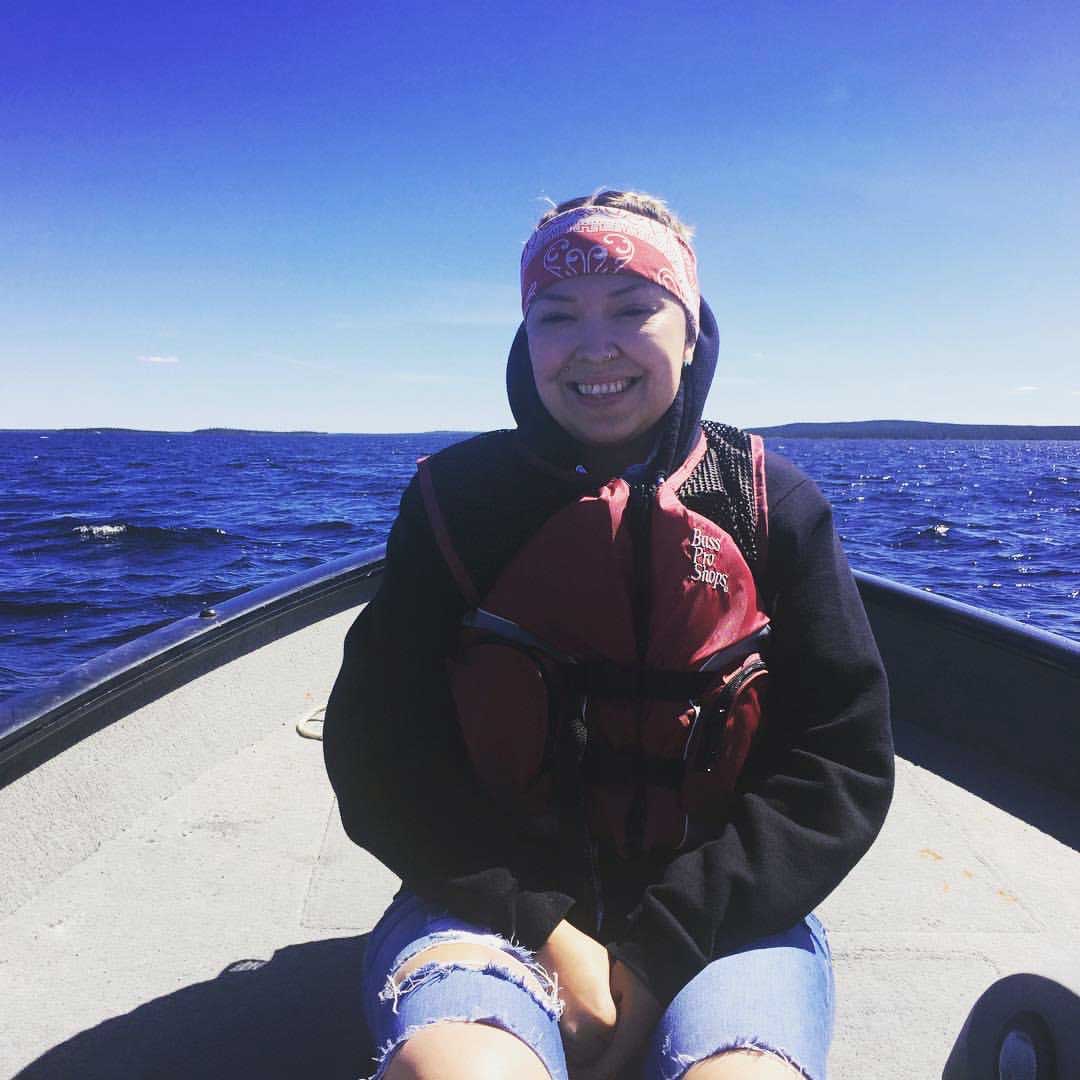

Stephanie Thorassie enjoys time on the water near Tadoule Lake. Photo courtesy of Stephanie Thorassie.

“We were told we weren’t good at these things,” Thorassie said. “But we always knew that we were great stewards of the land because we listened to the land. That’s a part of our soul that we connect to — the waters, and the caribou and the animals that are there.”

In addition to conserving the land, the initiative is also an opportunity for the five communities to create sustainable, land-based jobs. The Alliance is seeking to develop eco and cultural tourism opportunities in a way that honours the land.

“We want Canadians and people from around the world to see that there is a place like this that still exists,” Thorassie said.

Show your support for protecting the Seal River Watershed at bit.ly/SealWatershed.